Българският iGaming пазар добави десетки онлайн казина за 2024 – 2025 г., и за играчите е важно да отделят стабилната платформа от проект за един ден. Нашият гид обяснява на кои регулаторни данни, финансови метрики и технологични решения трябва да се обърне внимание. Останете с нас и изберете най-доброто казино за игра!

Ново онлайн казино 2025 в България – Най-добрите бонуси за българите!

Ново българско онлайн казино 2025: топ нови казина за български играчи

Нашата аналитична група анализира пазара за 2024 – 2025 г. и подбра платформи, които отговарят на строги критерии за сигурност, скорост на изплащанията и лоялна бонусна политика. В подбора влязоха само тези нови български онлайн-казина, където е потвърдена лицензията.

Кои онлайн казина са нови?

Към новите казина отнасяме платформи, които са се отворили или преоткрили през 2024 – 2025 г. Към категорията нови попадат не само оператори с български лиценз, но и международни сайтове, официално приемащи играчи от България и работещи на основание на чуждестранно разрешение. Основното условие е фактическото стартиране на продукта или радикалното обновление на платформата в посочения период.

Мотивация на играчите: защо избират ново онлайн казино

Нови и продължени лицензи: текущо състояние на пазара в България

Как да разберем, че новото онлайн казино е наистина безопасно

Нови казина: какви са ползите за играчите

Българският пазар отдавна е наситен с оператори, но новите проекти за 2024 – 2025 г. излизат с забележителен конкурентен набор от опции. Основните предимства са гъвкави бонусни правила, технологична платформа и кратък път от регистрацията до първия залог. Нека разгледаме детайлите.

Най-добрите бонуси с лоялни условия

Дизайн с идея: какво отличава новите казина

Как новите онлайн казина използват иновативни решения

Бърз вход в играта: съвременни методи за регистрация и проверка на играчите

Нови казина срещу стари оператори: ключови различия

- Бонусна политика: новите платформи намаляват изискванията за залагане и увеличават срока на промоциите; старите запазват класическите x35 и 7 дни.

- Технологии: новите проекти внедряват мобилен PWA-клиент, старите остават на десктоп версиите.

- Скорост на изплащане: новите платформи потвърждават заявки до 1 час, старите — до 24 часа.

- Игрово лоби: младите брандове добавят crash-игри и доставчици с Megaways, традиционните — се фокусират върху слотове с фиксиран RTP.

- Поддръжка: новите сайтове преминават към чат-ботове с Live-handover; утвърдените се ограничават с e-mail билети.

Класация и преглед на най-добрите нови казина за 2025 година

По-долу са представени 5-те най-добри онлайн казина, които бяха стартирани през последните години, имат действащи лицензи и приемат български играчи.

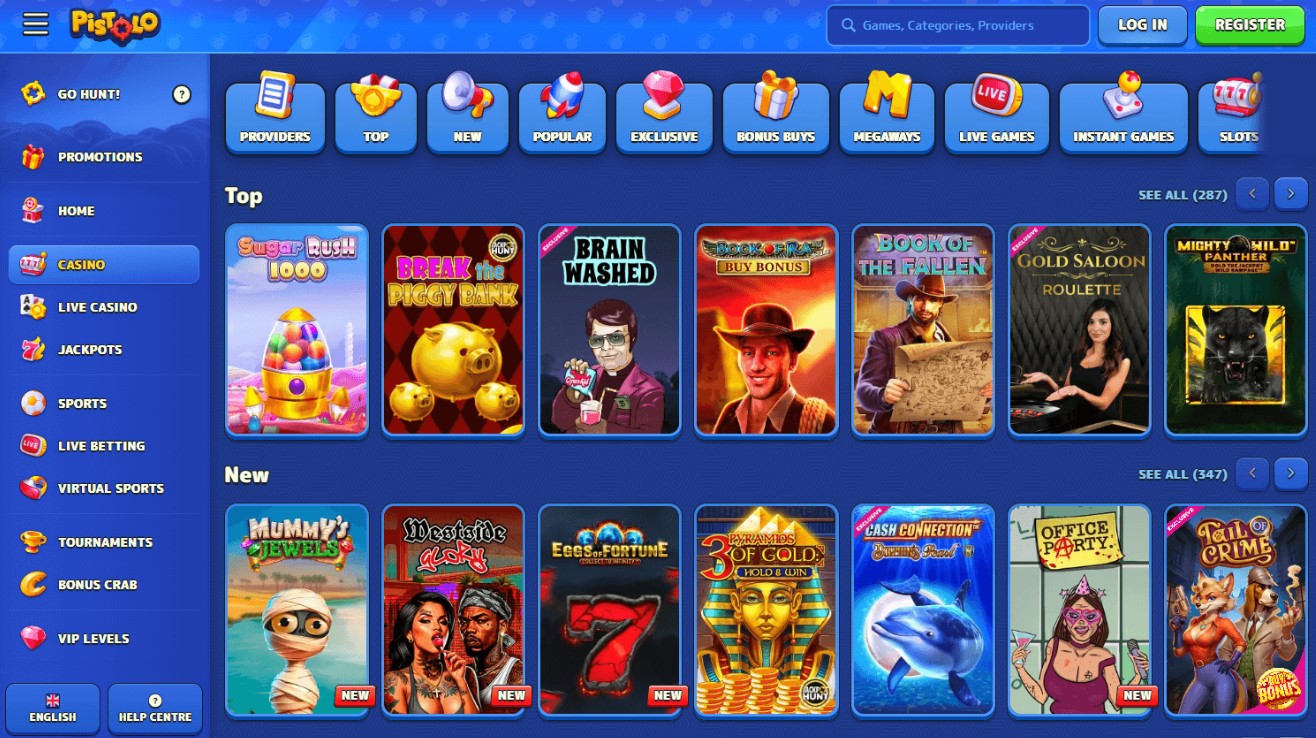

Pistolo

Pistolo – ново казино от 2025 година. Работи под лиценз на Anjouan. Платформата стартира с внушителен асортимент от над 9,000 игри, включително слотове, ексклузивни и моментални игри, настолни развлечения, лайв-казино и раздел със спортни залози. Дизайнът е в стил мексикански уестърн: ярки, контрастни цветове, анимационна графика и запомнящ се фирмен персонаж създават атмосфера на азарт и приключения. Новите играчи са посрещнати с приветствен бонус, а всяка седмица е достъпен Reload Bonus.

Предимства

- Широка гама от игри

- Седмични и месечни турнири

- Денонощна поддръжка

- Ексклузивни игри

Недостатъци

- Липса на мобилно приложение

- Няма телефонна поддръжка

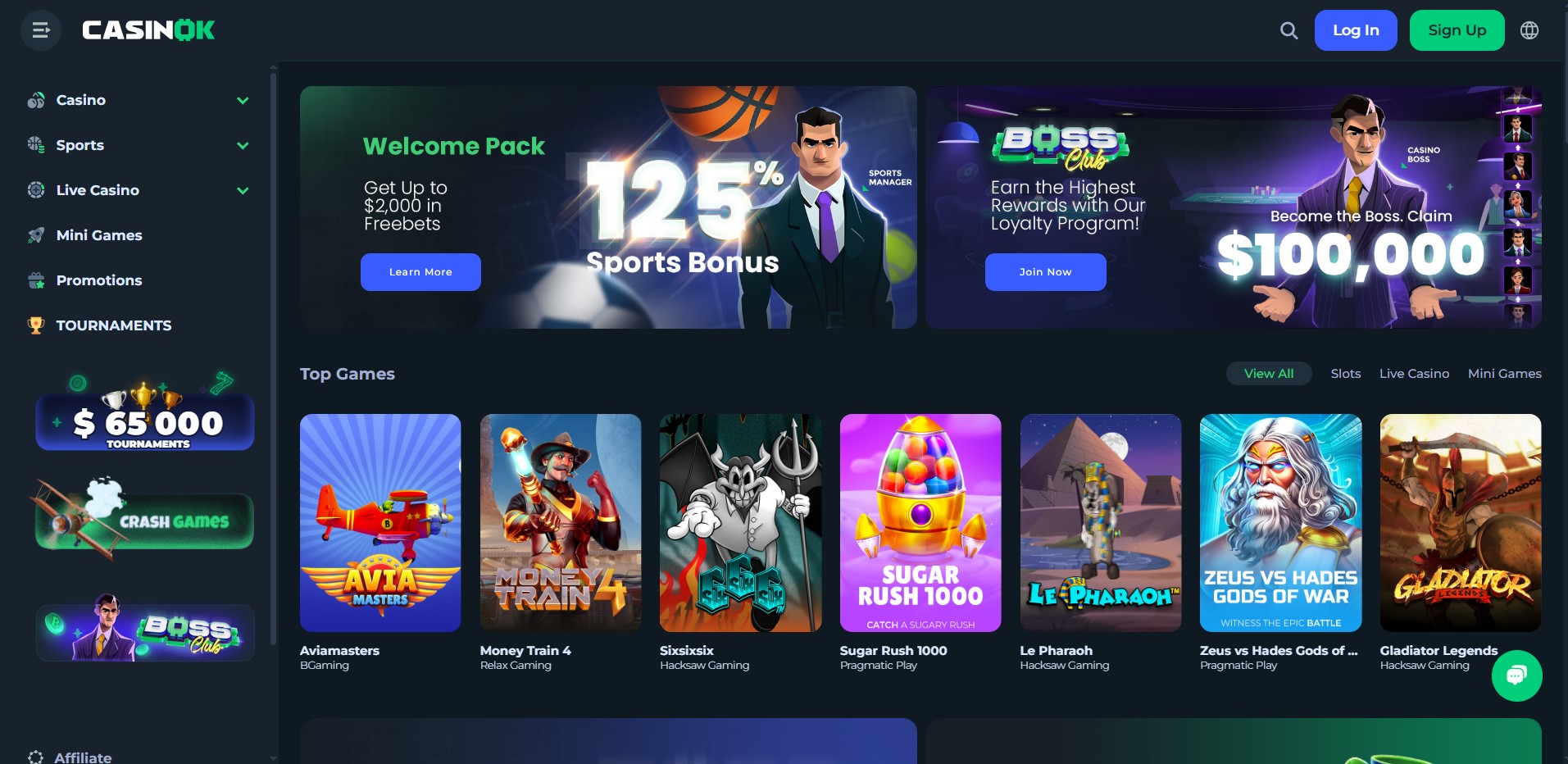

Casinok

Casinok – ново онлайн казино от 2025 година, ориентирано към крипто-плащания и работи с лицензия от Кюрасао. Платформата веднага предложи над 7,000 игри, сред които са представени слотове и популярни лайв-игри. В дизайна на сайта е поставен акцент върху съвременния стил и минимализма, преобладават тъмносини и черни цветове, създаващи атмосфера на технологичност и премиум-клас. На новите играчи е достъпен щедър приветствен пакет, а за любителите на спортни залози е предвиден отделен бонус.

Предимства

- Поддръжка на криптовалута

- Широк избор от игри

- Седмични и месечни турнири

- Денонощна поддръжка

Недостатъци

- Ограничен брой игрови категории

- Липсва мобилно приложение

- Няма ВИП програма

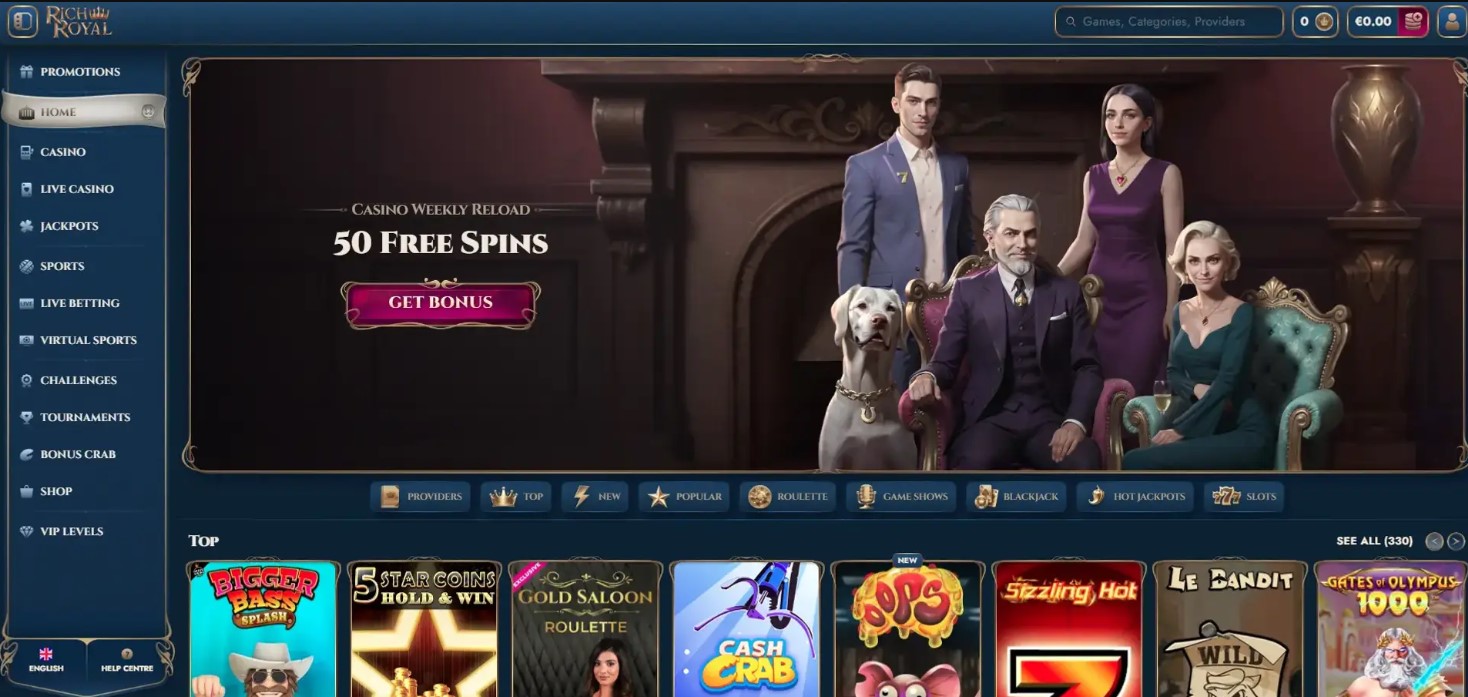

RichRoyal

RichRoyal – ново онлайн казино, стартирано през 2025 година под лицензията на Costa Rica Gambling. В началото операторът предложи впечатляващ асортимент: над 9,000 игри, включително слотове, джакпоти, live-казино, настолни и мигновени игри, както и пълноценен раздел за спортни залози. Дизайнът на платформата е изпълнен в тематика на лукс и статус, с акцент върху кралските цветове – злато, черно и пурпурно. Бонусната програма стартира с приветствен пакет.

Предимства

- Широк избор на игри

- Бонус Краб

- Собствен магазин с бонуси

- Денонощна поддръжка

Недостатъци

- Липса на мобилно приложение

- Няма телефонна поддръжка

JettBet

JettBet – младо онлайн казино, стартирало през 2024 година и работещо по лицензия от Кюрасао. Към момента на старта операторът представи на играчите повече от 4,000 игри, сред които лайв-казино, джакпоти, настолни игри и разнообразие от спортни залози. Тематичното оформление на платформата е вдъхновено от авиационната тематика, с акцент върху тъмносини и червени нюанси, които усилват атмосферата на динамика. За новите играчи е предвиден мощен приветствен бонус, както и отделно предложение за спортни залози.

Предимства

- ВИП програма с кешбек до 25%

- Собствен магазин с бонуси

- Седмични и месечни турнири

- Поддръжка на криптовалута

Недостатъци

- Липса на мобилно приложение

- Няма телефонна поддръжка

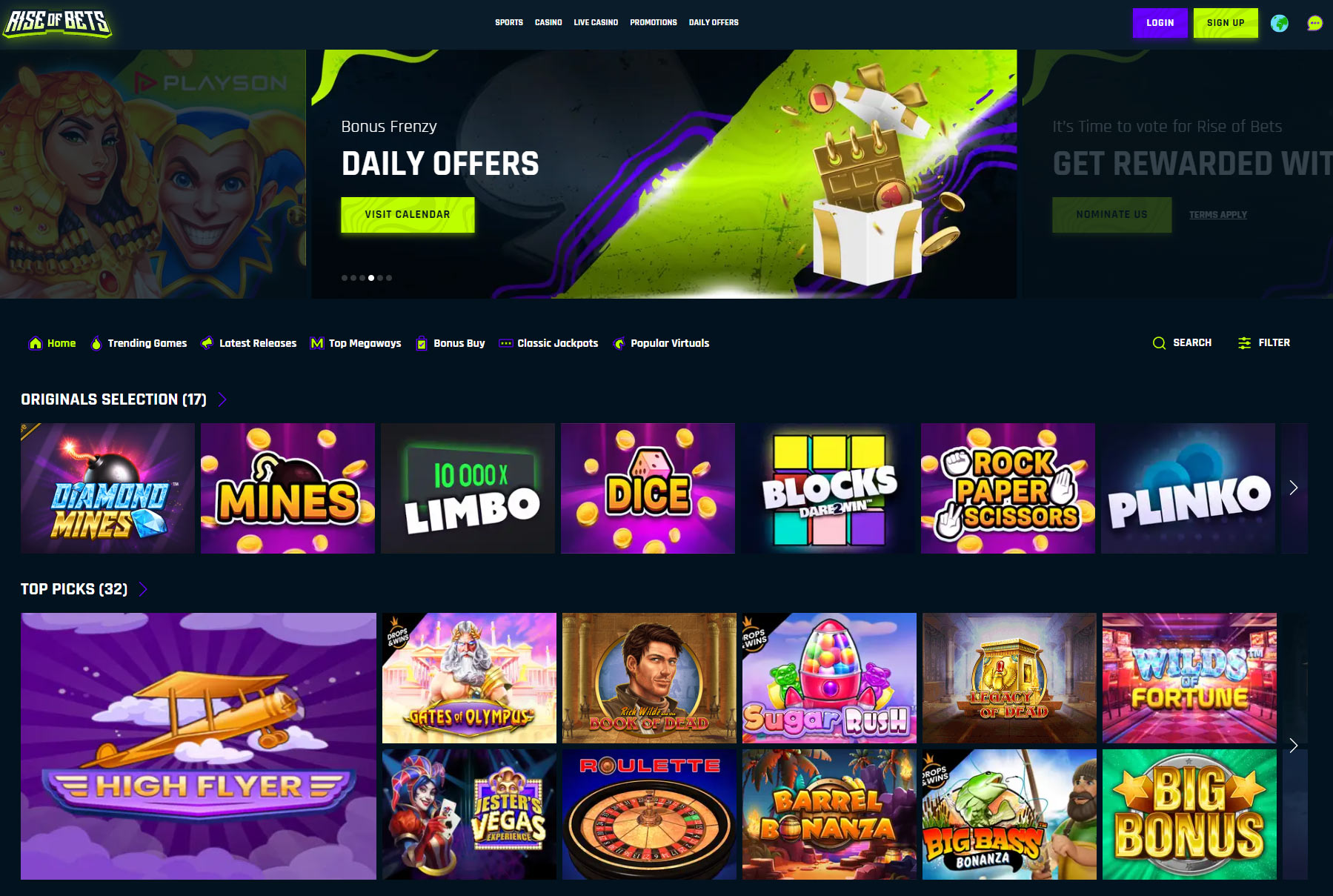

RiseofBets

RiseofBets – ново онлайн казино, стартирано през 2025 година с лицензия от Malta Gaming Authority. Игровият каталог включва над 3,500 забавления: слотове, моментални и настолни игри, раздел с лайв игри и спортни залози. Дизайнът на платформата е вдъхновен от света на фентъзито, с акцент върху тъмни цветове, мистична атмосфера и внимателно изработени тематични елементи. Новите играчи са посрещнати с бонус, а за любителите на спортните залози се предлага отделен приветствен бонус.

Предимства

- Поддръжка на редки спортове

- Уникален календар Rise of Bets

- ВИП програма

- Лицензия MGA

Недостатъци

- Липсва мобилно приложение

- Няма телефонна поддръжка

- Няма плащане с криптовалута

Таблица с характеристики на нови онлайн казина

| Име на казино | Година на откриване | Лицензия | Бонус | Видове игри | Рейтинг |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RichRoyal | 2025 | Коста Рика | Бонус 275% до 7 500 EUR и 225 FS + 1 BC | Слотове, джакпоти, live-казино, настолни, моментални игри и залози на спорт | 4.7/5 |

| Casinok | 2025 | Кюрасао | Бонус 300% до 5 500 EUR | Слотове, моментални игри, live-casino, настолни игри и залози на спорт | 4.7/5 |

| Pistolo | 2025 | Анжуан | Бонус 100% до 500 EUR и 200 FS | Слотове, ексклузивни и моментални игри, настолни развлечения, live-casino и залози на спорт | 4.8/5 |

| JettBet | 2024 | Кюрасао | Бонус 450% до 6 100 EUR и 425 FS | Слотове, live-casino, джакпоти, настолни игри и залози на спорт | 4.7/5 |

| RiseofBets | 2025 | Malta Gaming Authority | Бонус 100% до 1 000 EUR и 1 000 FS | Слотове, моментални и настолни игри, live-casino и залози на спорт | 4.7/5 |

Ръководство за избор на ново казино за играчи

Преди регистрация в нов проект за 2024 – 2025 г., проверете техническата база и асортимента на казиното. Шестте критерия по-долу помагат да се отсеят маркетинга и да се види как платформата реално работи.

Лицензия

Бонусно предложение

Скорост на изплащане на печалбите

Асортимент от игри

Поддръжка на платежни системи

Отзиви на играчи

Често задавани въпроси

Какви стъпки да предприемете, ако ново казино забавя изплащането на печалба?

Проверете лимита за време за Cash Out в правилата, уверете се, че KYC е завършен; поискайте статус в live-чата, запазете кореспонденцията; при закъснение над 24 часа подайте жалба до регулатора (Държавната комисия по хазарта на България, MGA, Curaçao) и платежния доставчик.

Може ли да се доверите на нови казина с ограничен игрови асортимент?

Да, ако са потвърдени лицензията и одитът на RNG; съкратеният каталог често е свързан с незавършени договори с агрегатори и не влияе на честността на изплащанията.

Имат ли новите казина лимити на печалбата?

Почти всички поставят дневен или месечен таван (например, 100,000 BGN на ден); точните цифри са посочени в T&C и зависят от VIP нивото и избрания метод за теглене.

Какво да направите, ако се сблъскате с технически проблеми в ново казино?

Изчистете кеша на браузъра, опитайте друго устройство; направете скрийншот на грешката и се обърнете към live-чата; при повторение изпратете тикет с детайли за ОС, браузъра и времето на грешката.

Какво да направите, ако ново казино не работи без VPN в България?

Проверете дали е разрешен достъпът за играчи от България; поискайте огледален домейн от съпорта; имайте предвид, че играта чрез VPN може да наруши правилата и да анулира печалбите.

Защо в новите казина понякога няма live-игри?

Live-масите изискват отделен лиценз и договори с доставчици (Evolution, Pragmatic Live); повечето оператори стартират този раздел след набиране на критична аудитория.